In the operating world, landing a “Whale”—a Fortune 500 client that generates 40% of your revenue—is a cause for celebration. It validates the product, funds the payroll, and feeds the ego. In the Private Equity world, that same Whale is treated as a toxic asset that can kill a transaction before the LOI is even signed.

We call this the Whale Paradox: The revenue quality that helps you survive the early years is often the exact structural flaw that prevents you from exiting at a premium. I recently reviewed a B2B services firm with $15M EBITDA. On paper, it was a prime target for a platform acquisition. But 45% of that EBITDA came from a single logistics giant. The multiple offered wasn’t the standard 10x; it was 6x, with 40% of the proceeds tied up in a three-year earnout. The market didn’t see $15M in profit; it saw a single point of failure.

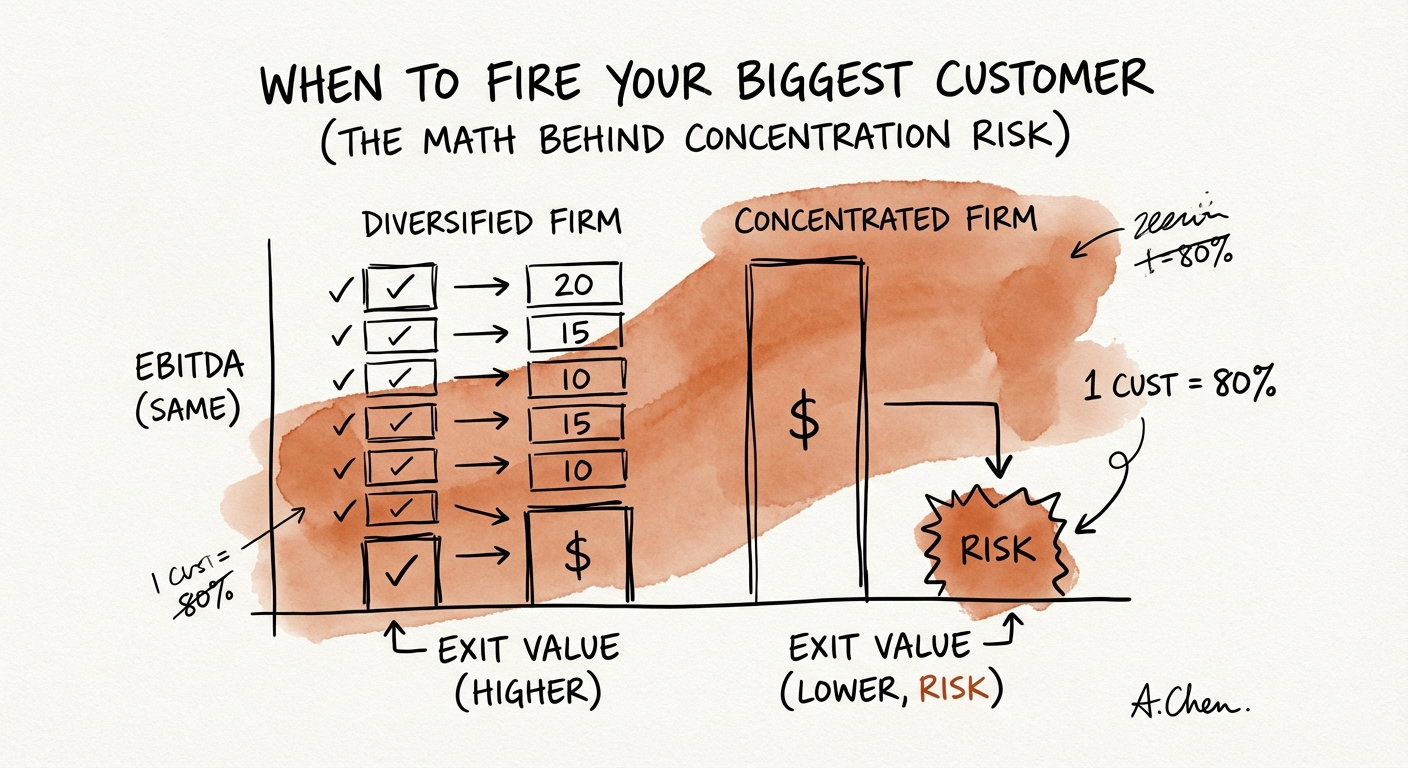

For Operating Partners and Founders, the math is brutal. Data from Focus Investment Banking suggests that customer concentration above 30% can reduce transaction valuation by 20-35%, or cause buyers to decline the opportunity outright. If you are prepping a portfolio company for sale in 2026, you don’t just need to grow revenue; you need to de-risk it. Sometimes, that means firing your biggest customer.

Valuation is not just a multiple of EBITDA; it is a multiple of predictable EBITDA. When a single customer controls your P&L, you don’t own a business; you own a sub-contractor agreement. Buyers price this fragility aggressively.

According to 2025 deal flow analysis, buyers categorize concentration risk into three specific tiers:

Let’s look at the math. Suppose you have two firms, both doing $5M EBITDA.

That $20M gap is the cost of your Whale. But it gets worse. Whales often demand volume discounts, custom integrations, and 24/7 support, eroding gross margins. We often find that while a Whale contributes 40% of revenue, they may contribute only 15% of actual profit once fully burdened costs are applied. In this scenario, the client is not just a valuation risk; they are a margin diluter. This is exactly why we analyze customer concentration thresholds during due diligence before we even advise on the roadmap.

If you are staring at a 40% concentration issue 18 months before an exit, you have three options. “Hope” is not one of them.

The most palatable option is to grow the rest of the business so fast that the Whale becomes a Minnow. If your Whale pays you $5M, you need to add $5M in new ARR from other sources to halve their concentration impact. This requires aggressive investment in sales and marketing—often using the cash flow from the Whale to fund the acquisition of their replacements.

If you can’t outgrow them, you must lock them down. Convert the relationship from a “vendor” status to a “partner” status with multi-year, non-cancelable contracts. While this doesn’t fix the concentration number, it mitigates the flight risk, which can sometimes salvage the valuation multiple.

This is the contrarian move that elite operators make. If your Whale is low-margin and high-maintenance, fire them. Or, more politely, raise their prices by 40% to match the risk premium they impose on your business. One of two things will happen:

For a detailed breakdown of how to restructure revenue for valuation, read our guide on pivoting from project to recurring revenue. The math is clear: A smaller, diversified business is often worth more than a larger, concentrated one. Don't let vanity revenue kill your exit.