You have successfully scaled your portfolio company, expanded EBITDA margins, and brought a strategic acquirer to the table. The valuation gap is $20M. To bridge it, the buyer offers a classic solution: a $20M earnout tied to future performance. On the spreadsheet, your exit multiple looks like a home run. In reality, you have likely just negotiated a lawsuit, not a payment.

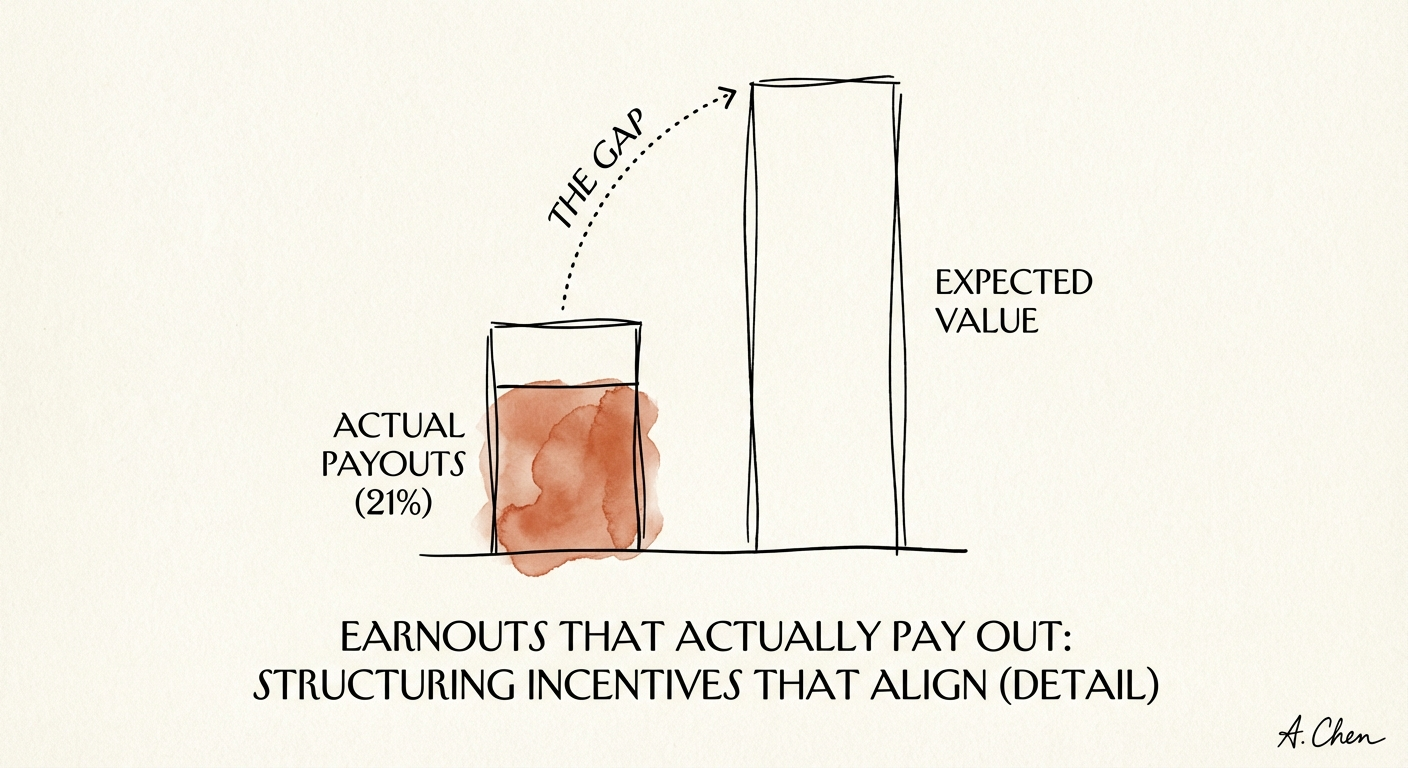

The data on earnouts is sobering. According to the 2025 SRS Acquiom Deal Terms Study, the average earnout pays just 21 cents on the dollar. Even among the deals that trigger some payment, sellers typically realize only 50% of the maximum value. For a Private Equity Operating Partner, this represents a massive leakage of value. You are essentially underwriting an option for the buyer—giving them the upside of your asset's performance while you retain the execution risk, often without the control required to manage it.

The failure mode is rarely the team's inability to execute. It is structural. Most earnouts are designed with "hope" as a strategy—hoping the buyer doesn't reallocate resources, hoping corporate overhead doesn't crush the P&L, and hoping integration chaos doesn't stall the very growth metrics the payout depends on. When you sell a portfolio company, an earnout should not be treated as a lottery ticket. It must be engineered as a secured obligation, protected by covenants as rigorous as a credit agreement.

If you must accept an earnout to clear the market clearing price, you need to structure it to remove "Buyer Discretion" from the equation. The debate between Revenue and EBITDA metrics is the first battleground. While conventional wisdom suggests Revenue is safer (harder to manipulate), recent data suggests a nuance: sellers with EBITDA-based earnouts actually maximize their payouts nearly 66% of the time, compared to just ~33% for revenue-based structures. Why? Because revenue targets are often set at unrealistic "synergy-fueled" growth rates, whereas EBITDA targets are often grounded in historical efficiency baselines that a disciplined operator can control.

Never rely on a generic GAAP definition of EBITDA in an earnout agreement. You must negotiate a "Frozen GAAP" clause, ensuring that the accounting principles used to calculate the earnout match exactly those used in your historical financials. Furthermore, specifically exclude:

Buyers love to promise "commercially reasonable efforts" to support the business post-close. In court, this phrase is notoriously slippery. Replace it with Specific Performance Covenants:

Without these guardrails, a buyer can simply "starve" your unit to boost their own short-term cash flow, causing you to miss the growth target that triggers your payment.

What happens if your acquirer gets acquired 12 months later? Or if they divest your division? Every earnout must include a mandatory acceleration clause: upon a Change of Control or divestiture of the acquired asset, the maximum remaining earnout is deemed earned and paid immediately in cash. You cannot allow your earnout to become a liability on their balance sheet that they trade away.

For a PE sponsor, the goal is to exit cleanly. An earnout that requires two years of litigation to collect is a failed exit. The key to "earning out" is often the Integration Shield. You must negotiate a 12-to-24-month "hands-off" period where the acquired entity operates semi-autonomously. If the buyer insists on immediate heavy integration (e.g., forcing a migration to a Salesforce instance that isn't ready), the earnout milestones must be adjusted downward to account for the disruption.

We recently advised a firm selling a specialized IT services unit. The buyer proposed a $10M earnout tied to 20% YoY revenue growth. We countered with a structure that allowed for "Catch-Up" provisions: if the Year 1 target was missed due to integration delays, the shortfall could be made up in Year 2. We also inserted a "Deemed Revenue" clause: if the buyer cross-sold the target's product as part of a bundle, 100% of the list price was attributed to the earnout calculation, regardless of the discount they gave on the bundle.

When preparing your portfolio company for sale, conduct a pre-sale readiness assessment that anticipates these arguments. If you have clear, documented EBITDA add-backs and a history of hitting forecasts, you have leverage to demand lower earnout components. If your revenue is lumpy or suffers from high customer concentration, buyers will demand larger earnouts to de-risk.

Ultimately, an earnout is a partnership mechanism disguised as a pricing mechanism. If the incentives align, it works. If they don't, you are simply financing the buyer's acquisition of your business with your own lost capital. Structure it with the cynicism of a lender and the precision of an engineer, and you might just see that 21 cents turn into a dollar.