In the high-stakes world of Mergers and Acquisitions, you diligence everything. You audit the financials, you scrutinize the legal contracts, and you interview the sales leaders. Yet, the asset you are often paying the highest multiple for—the proprietary software—is frequently treated as a black box. This is a critical error. Technical debt is not merely an engineering nuisance; it is a financial liability that behaves exactly like high-interest debt.

When you acquire a company with significant technical debt, you are inheriting a hidden lien on future cash flows. According to research by McKinsey & Company, technical debt can amount to 20-40% of the value of the entire technology estate before depreciation. For a Private Equity sponsor, this means up to 40% of the asset you just bought might be effectively underwater, requiring massive remedial CapEx before it can scale.

The cost of ignoring this reality is staggering. The Consortium for Information & Software Quality (CISQ) estimated the Cost of Poor Software Quality (CPSQ) in the U.S. alone at $2.41 trillion. In an M&A context, this manifests as "EBITDA leakage"—capital that should be fueling growth is instead diverted to fixing bugs, patching security holes, and untangling spaghetti code.

We must shift the narrative. We are not looking for "perfect code"—that doesn't exist. We are looking for quantifiable risk. We need to measure the debt to price it into the deal.

To diligence technical debt effectively, you must move beyond qualitative developer interviews and look at hard data. Just as you wouldn't accept "our finances feel good" as an answer, you shouldn't accept "our code is clean." Here are the four non-negotiable metrics for your technical due diligence checklist.

This measures the number of linearly independent paths through a program's source code. In simple terms: how tangled is the logic? High cyclomatic complexity correlates directly with defect rates and maintenance costs. If a core revenue-generating module has a complexity score off the charts, it is a ticking time bomb that will require expensive refactoring.

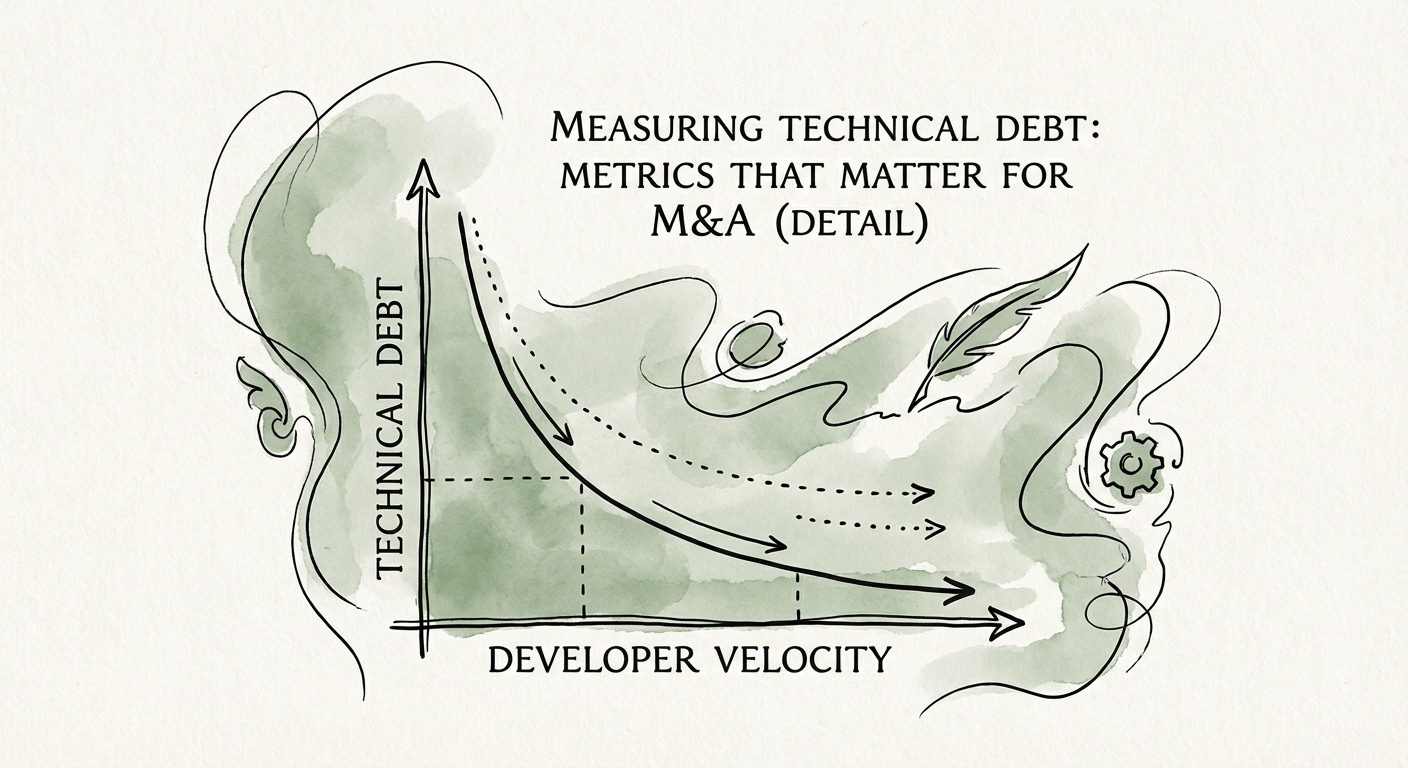

Code Churn measures the percentage of a developer's own code they have to rewrite within 2-3 weeks of writing it. High churn indicates fragility; the developers are struggling to make features stick. Gartner data suggests that organizations actively managing technical debt achieve at least 50% faster delivery times. If churn is high, your post-acquisition 100-day plan for product innovation is already at risk.

It is not enough to have code; you must have the insurance policy that comes with it. Low test coverage (typically under 75%) implies that every new feature added has a high probability of breaking existing functionality. This creates a "fear culture" where engineers are afraid to deploy updates, slowing your time-to-market significantly.

This is your proxy for "Key Person Risk." If the code is complex and undocumented, the knowledge lives exclusively in the head of a founding engineer. If that engineer leaves post-close (which they often do), your asset's value plummets. Automated tools can scan repositories to determine the ratio of comments to code, providing a clear signal of maintainability.

Once you have these metrics, what do you do? You don't necessarily kill the deal. Instead, you use the data to structure a better one. Technical debt is a lever for negotiation.

For Portfolio Paul, the goal is not engineering purity; it is predictability. By quantifying technical debt during the diligence phase, you transform an unknown risk into a managed liability. You ensure that the capital you inject post-acquisition goes toward value creation, not interest payments on someone else's bad decisions. In the modern economy, code quality is asset quality.