There is a conversation happening in boardrooms across the middle market right now that sounds like two people speaking different languages. On one side sits the Operating Partner, looking at a spreadsheet. They see missed revenue targets, slipping product release dates, and a bloated R&D budget that doesn't seem to produce features. Their language is EBITDA, speed-to-market, and capital efficiency.

On the other side sits the CTO, talking about refactoring, microservices, and technical debt. They are explaining why the roadmap is delayed (again) and why they need to hire three more senior engineers just to keep the lights on.

The Operating Partner hears excuses. The CTO feels misunderstood. And the portfolio company sits stalled in the middle, bleeding value.

Here is the reality: Technical debt is financial debt. It behaves exactly like a high-interest loan. You took a shortcut two years ago to close a deal (principal), and now your engineering team spends 33% of their week fixing bugs instead of building new revenue-generating features (interest).

According to Stripe's Developer Coefficient report, the average developer spends 13.5 hours per week dealing with technical debt and bad code. That is not just an annoyance; it is a massive capital inefficiency. If you have a $10M engineering payroll, you are effectively burning $3.3M annually on maintenance that often gets disguised as R&D. That is $3.3M of EBITDA suppression hiding in plain sight.

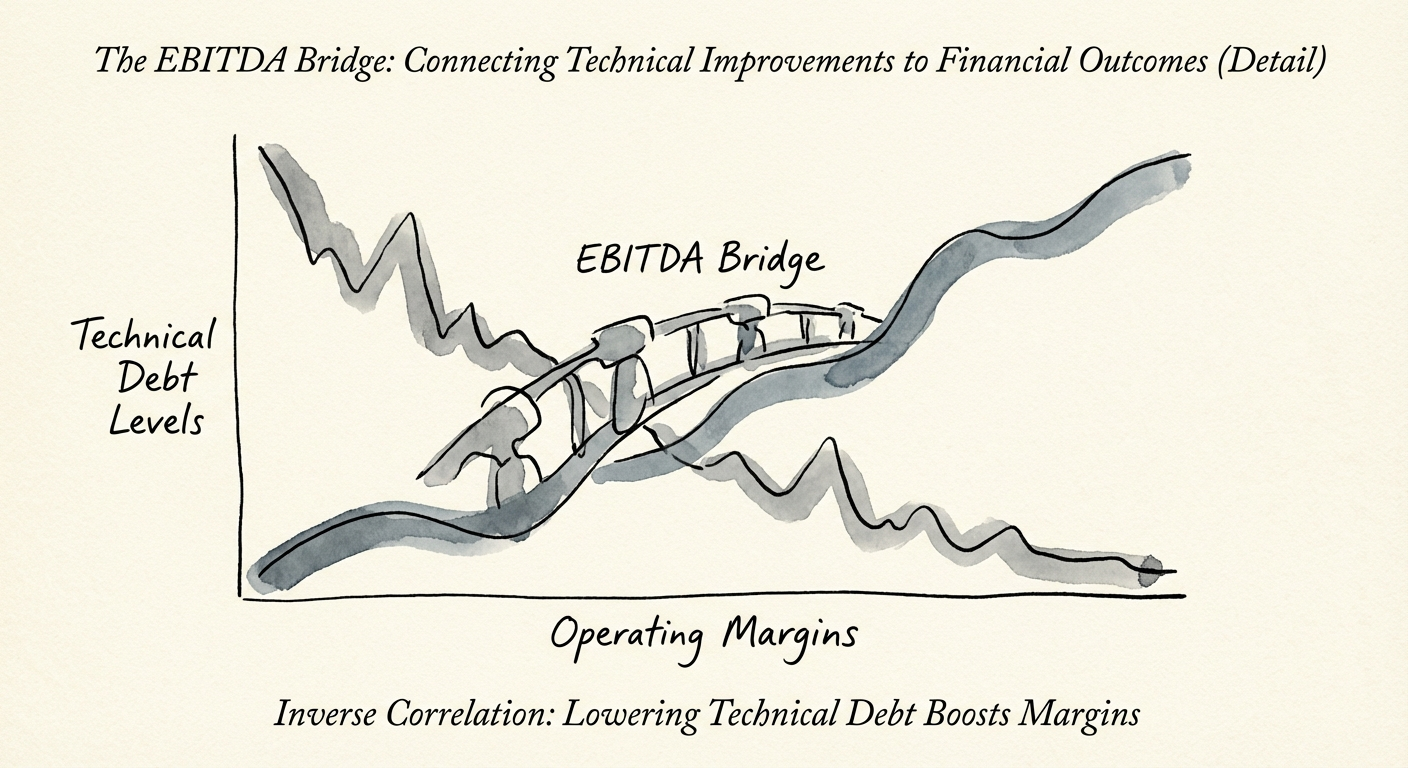

For a Private Equity sponsor, this "Tech Debt Tax" is the difference between a 3x and a 5x return. The problem isn't that the code is ugly; the problem is that the Operating Partner doesn't know how to quantify the cost of that ugliness in dollar terms. We need a bridge.

To fix this, we must stop treating engineering as a black box and start measuring "Technical EBITDA." This means translating abstract engineering concepts into the financial metrics that drive the investment thesis. Here are the three pillars of the EBITDA Bridge.

In a healthy SaaS company, 70-80% of engineering time should be spent on innovation (new value). In high-debt companies, that number often flips. We recently audited a portfolio company where 65% of engineering cycles were consumed by "unplanned work"—patches, hotfixes, and stability firefighting.

When you remediate technical debt, you don't just make developers happier. You shift resources from low-value maintenance (OPEX behavior) to high-value innovation (CAPEX behavior). This shift directly impacts the P&L. If you can reclaim 20% of your engineering capacity by automating a deployment pipeline, you have effectively hired 20% more engineers without adding a dime to payroll. That is pure margin expansion.

Poor code quality travels downstream. A bug caught in design costs $100 to fix. According to the Consortium for Information & Software Quality (CISQ), that same bug caught in production costs 100x more. Why? Because it triggers a Tier 1 support ticket, escalates to Tier 2, distracts a Customer Success Manager, and finally pulls a senior engineer off a strategic project to patch it.

We call this the "Support Tax." By correlating Defect Density (bugs per release) with Support Costs, we can mathematically prove that investing $200k in automated testing will save $500k in support labor and churn reduction over 12 months. That is an EBITDA add-back waiting to be claimed.

The most compelling data comes from McKinsey's Developer Velocity Index (DVI). Their research shows that companies in the top quartile of developer velocity don't just ship faster; they generate 20% higher operating margins than their bottom-quartile peers. Speed is efficiency. Efficiency is margin.

When a CTO asks for budget to pay down technical debt, the answer shouldn't be "no." It should be: "Show me how this specific refactor moves us from the bottom quartile to the top quartile, and what that does to our unit economics." This is the core of Technical Due Diligence—not just checking for open-source licenses, but assessing the velocity potential of the asset.

You cannot manage what you do not measure. To cross the EBITDA Bridge, Operating Partners must demand a "Technical Quality of Earnings" assessment. This is not a code review; it is a financial impact analysis of the engineering organization.

When you go to market, you want to sell a platform, not a project. A platform has predictable delivery, low maintenance costs, and high margins. A project requires heroics to keep running.

By building the EBITDA Bridge today, you are doing more than fixing bugs. You are engineering a higher multiple. You are proving to the next buyer that the 20% EBITDA margin is durable, scalable, and not dependent on a room full of burnt-out engineers holding the system together with duct tape. That is how you turn code into cash.