You have scrutinized the P&L, stress-tested the revenue retention, and interviewed the sales leader. The quality of earnings (QofE) report looks solid. But under the hood of that SaaS platform you are about to acquire lies a liability that does not show up on a standard balance sheet: technical debt. In 2025, it is the silent killer of post-close value creation.

When you buy a software company, you are buying its future cash flows, but you are also inheriting its past engineering decisions. If those decisions were optimized for speed at the expense of stability—what we call "mortgaging the codebase"—you aren't just buying a product; you are buying a remediation project. Recent data from the 2025 Black Duck Open Source Risk report is alarming: 96% of audited M&A transactions contained unpatched security vulnerabilities, and 85% had license conflicts. You aren't just buying code; you're buying liability.

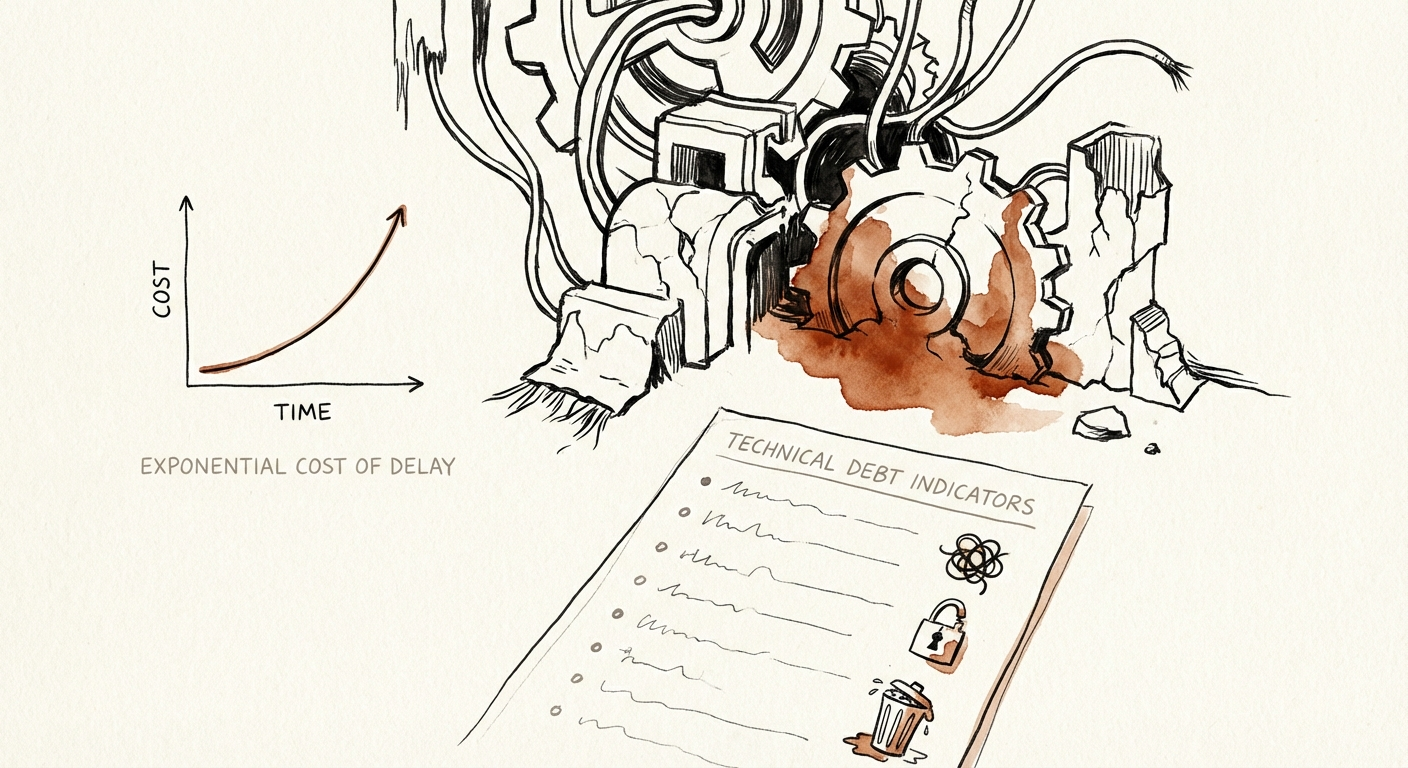

Technical debt isn't just an engineering annoyance; it is financial debt with variable interest rates. When your roadmap stalls because developers are spending 23% of their time fixing bugs instead of shipping features, your hold period extends, and your IRR compresses. You need to look past the product demo and interrogate the code itself. You need a diagnostic framework that translates "spaghetti code" into "EBITDA risk."

We do not need to read every line of code to spot a disaster. In our technical due diligence assessments, we look for these eight quantitative indicators that signal deep structural rot.

Cyclomatic complexity measures the number of independent paths through a block of code. In plain English: how tangled is the logic? A score under 10 is healthy. A score over 15 indicates code that is exponentially harder to test and maintain. Research shows that high-complexity code requires 2.5x to 5x more maintenance effort than clean code. If the core IP has a score of 50+, you are looking at a full rewrite, not a refactor.

Scan the commit history. If 80% of the code in the last 12 months was written by one person—usually the founding CTO who "keeps it all in their head"—you have a single point of failure. This isn't just a retention risk; it's an undocumented asset risk. When that person leaves (and they will, post-earnout), the asset value drops to zero because no one else can operate the machine.

Check the ratio of bugs found in development vs. production. A healthy engineering team catches 90% of issues before deployment. If the target company is constantly patching live environments, your cost basis is exploding. NIST data confirms that fixing a defect in production costs 30x more than fixing it during the design phase. A high production defect rate is a leading indicator of margin erosion.

While 80% coverage is the gold standard, we often see targets with < 20%. Low test coverage means every new feature carries a high risk of breaking existing functionality. This creates "fear-driven development," where engineers refuse to touch legacy modules, paralyzing your roadmap.

Automated tools can instantly spot duplicated code blocks. Anything above 10-15% suggests a sloppy engineering culture or a lack of abstraction. Duplicate code means duplicate bugs: fix an issue in one place, and you likely missed it in three others.

How old are the third-party libraries? If the core framework hasn't been updated in 3 years, you aren't just facing technical obsolescence; you are facing unpatched security holes. As noted in The $2M Mistake, relying on "End of Life" libraries can force an immediate, unplanned platform migration post-close.

High code churn (frequent rewrites of the same modules) coupled with low comment density is the hallmark of "trial and error" programming. It indicates the team doesn't understand the problem they are solving. It’s the coding equivalent of throwing spaghetti at the wall.

Run a standard linter (static analysis tool). We don't care about a few errors; we care about the trend. Is the number of violations increasing month-over-month? If so, the team is accumulating debt faster than they are paying it down. You are acquiring a sinking ship.

Identifying these flags is step one. The strategic move is converting them into deal terms. You do not walk away from a deal just because of technical debt—every company has it. You walk away if the price doesn't reflect the cost of remediation.

If our audit reveals a $500k cost to upgrade a legacy database or a 6-month roadmap delay to pay down debt, that value must come out of the purchase price. We recommend structuring a "Technical Remediation Holdback"—a portion of the purchase price held in escrow and released only when specific technical milestones (e.g., SOC 2 compliance, platform upgrade) are met.

Post-close, do not push for "more features" immediately. Use the first quarter to stabilize the asset. As detailed in our EBITDA Bridge framework, investing in debt reduction early increases developer velocity (and therefore capital efficiency) for the remainder of the hold period.

Technical debt is invisible to the financial auditor, but it is glaringly obvious to the technical operator. Do not buy a black box. Open the code, run the diagnostics, and price the asset based on reality, not just the pitch deck.