You bought the division for 6x EBITDA. The parent company wanted it gone, the multiple was attractive, and your investment committee saw an arbitrage opportunity. On paper, it looks like a standard platform play. In reality, you haven't bought a company; you've bought a customer list and a group of employees who just lost their email access.

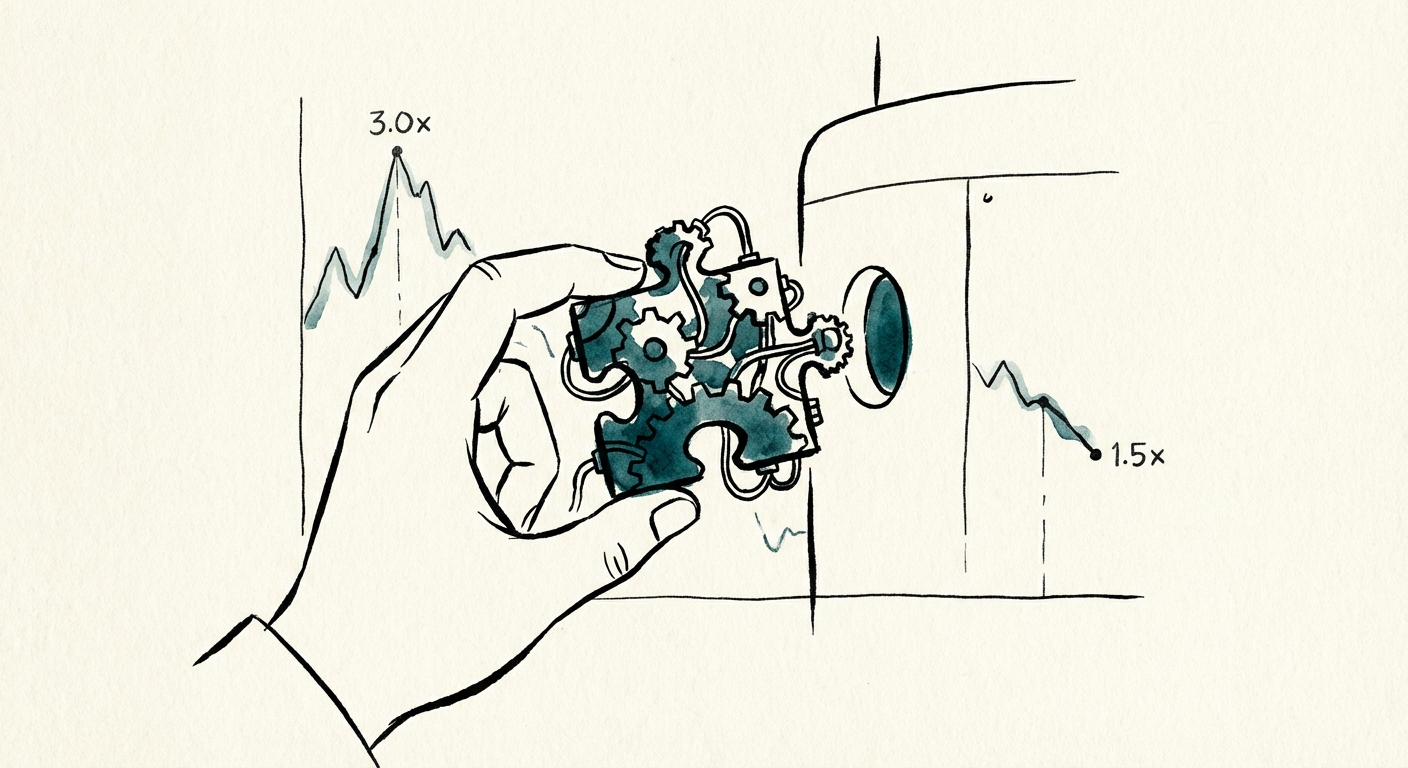

For the last decade, carve-outs were the reliable alpha generator for private equity. Pre-2012, they delivered a 3.0x MOIC, significantly outperforming standard buyouts. That advantage has evaporated. New data reveals that the average carve-out now delivers just 1.5x MOIC, lagging behind the broader buyout average of 1.8x. The reason isn't the asset quality; it's the underestimated complexity of separation.

When you buy a standalone company, you acquire a functioning nervous system—HR, IT, Finance, and Legal are operational. In a carve-out, you are performing a transplant without a donor body. The "Missing Infrastructure Tax"—the cost to stand up these functions from scratch—is rarely fully priced into the deal model. Worse, the Transition Services Agreement (TSA), designed as a temporary bridge, often becomes a permanent crutch, draining cash flow and delaying the very operational improvements that justified the acquisition.

The single biggest destroyer of value in a carve-out is the Transition Services Agreement. Most deal teams model a 12-month TSA with a linear ramp-down. The reality is far messier. Industry benchmarks show that typical TSA exits now drag on for 12 to 24 months, with costs often escalating as extensions trigger penalty rates.

IT is no longer a support function; it is the business. In a carve-out, you aren't just migrating data; you are disentangling a spaghetti code of shared licenses, custom ERP modules, and cybersecurity dependencies. Cloud migration cost overruns are common, but in a carve-out, they are existential.

Unlike a bolt-on acquisition where you integrate the target into your platform, a carve-out requires a "Standup First" mentality. However, the best performers don't just replicate the parent's bloated processes. They use the disruption to implement a lean, fit-for-purpose operating model immediately. Budget benchmarks suggest that allocating anything less than 5-7% of deal value for separation (vs. 3% for standard integration) ensures failure.

The only way to restore the 3.0x MOIC potential of a carve-out is to treat the separation as a transformation event, not an administrative burden. You need to speak fluent EBITDA and fluent DevOps simultaneously.

Do not let the deal team manage the separation. You need a dedicated SMO launched before the deal closes. Their sole KPI is "Days to TSA Exit." Every week on the TSA is a week you aren't controlling your own data, your own customer experience, or your own costs.

Resist the urge to "lift and shift" the parent company's legacy ERP. It is likely over-engineered for your new, smaller entity. Instead, use the carve-out as a forcing function to adopt a modern, consolidated tech stack. It is often faster and cheaper to implement a new NetSuite instance than to clone a customized SAP environment.

Negotiate TSAs with punitive price escalators after Month 6. This seems counter-intuitive—why penalize yourself? Because it aligns incentives. It forces your management team to prioritize the standup. If the TSA is comfortable, nobody leaves.

Carve-outs are not for tourists. They require a level of operational rigor that standard buyouts do not. But for the operator who can navigate the complexity, the reward is real: you can buy assets at 6x that trade at 12x once they are standalone. The spread isn't in the financial engineering; it's in the execution.