You’ve found the perfect target. $20M ARR, 25% EBITDA margins, growing 15% YoY. The Information Memorandum (IM) reads like a dream until you hit the customer breakout slide. Customer A is 28% of revenue. Customer B is 14%.

Suddenly, you aren’t buying a diversified platform; you’re buying a subcontractor for Customer A. In the eyes of an investment committee or a lender, this isn’t a growth story; it’s a binary risk event.

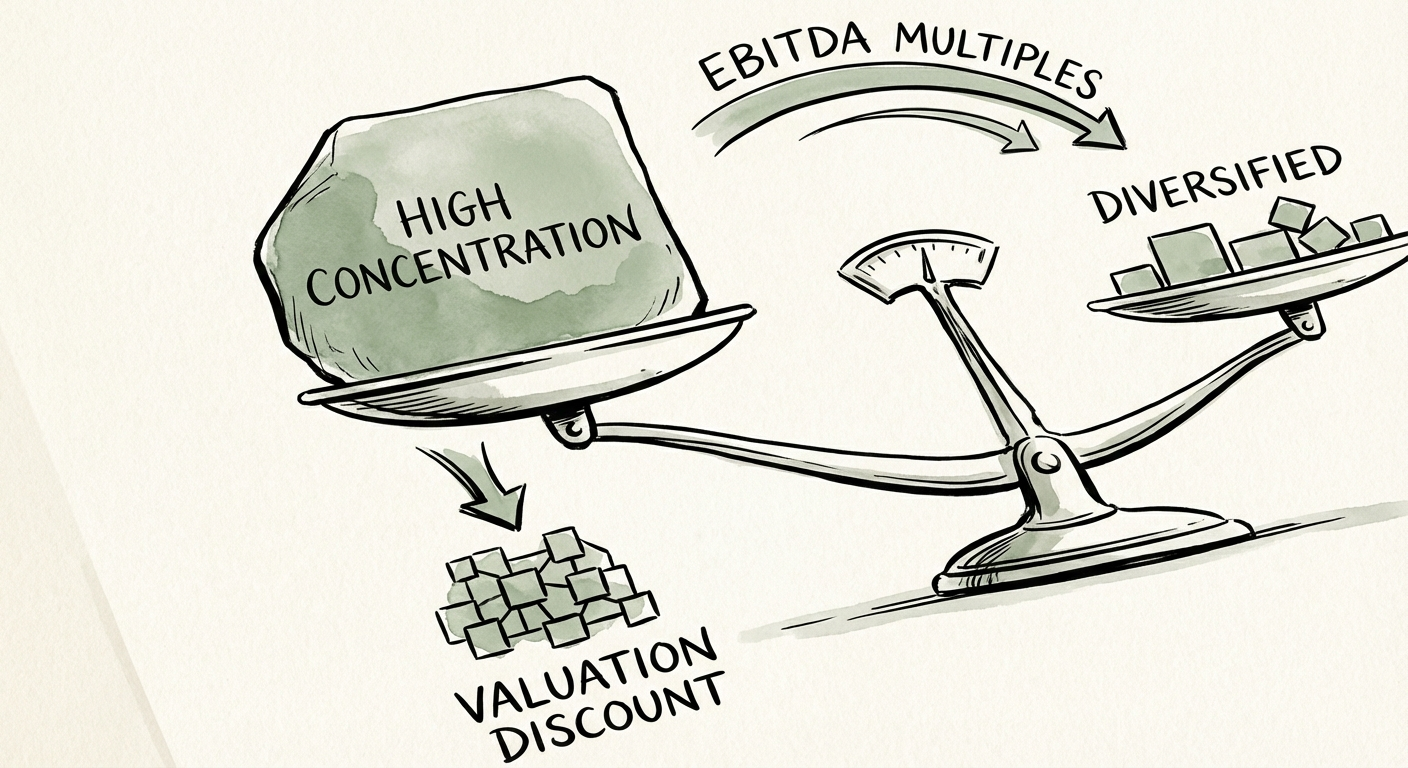

The market data on this is unforgiving. Concentration above 20% with a single customer is the threshold where premium multiples die. According to data from Focus Investment Banking, customer concentration >30% often renders a business unsellable to conventional buyers or triggers valuation discounts of 20-35%. It doesn’t matter if that customer is Amazon or Lockheed Martin; if they sneeze, your portfolio company catches pneumonia.

For Operating Partners, the danger isn’t just the risk of churn—it’s the quality of that revenue. "Whale" customers often wield their leverage to demand lower pricing, extended payment terms, and custom features that distract engineering from the roadmap. You might be acquiring $5M of revenue from that whale, but if it comes at 10% gross margin while the rest of the business runs at 70%, your blended metrics are lying to you.

Don't just flag concentration as a risk in the diligence log and move on. You need to stress-test the structural integrity of that revenue. Use this diagnostic framework to determine if the concentration is fatal or manageable.

Calculate the Unit Economics of the Whale strictly in isolation. Often, you will find that the largest customer is actually the least profitable. Customer Concentration Thresholds dictate that you must analyze Gross Margin relative to the company average. If the Whale's GM is 40% while the company average is 65%, that revenue is "empty calories." You are servicing them at the expense of scalable growth.

How hard is it for them to leave? High concentration is acceptable if the switching costs are insurmountable. Look for:

Who owns the relationship? If the founder is the only person who talks to the Whale's VP, you have a Revenue Quality crisis waiting to happen. A healthy Whale relationship is "multi-threaded"—your VP of Engineering knows their CTO, your CS team knows their users, and your CFO knows their procurement lead. If the founder leaves post-close, does the relationship leave with them?

Review the Change of Control (CoC) provisions. Does the acquisition trigger a renegotiation? Worse, does the contract have a "Termination for Convenience" clause? If a customer representing 30% of revenue can walk away with 30 days' notice for no reason, you cannot underwrite that revenue as recurring.

Run a downside scenario: If the Whale churns on Day 1, can you cut costs fast enough to survive? Often, Whale accounts require dedicated headcount (Customer Success Managers, custom dev teams). If the revenue vanishes, do those costs vanish too, or are they fixed overhead that will drag the remaining business into the red?

If the stress test reveals high risk, you don’t necessarily have to kill the deal. You move from diligence to engineering.

The most effective play is to isolate the concentration risk financially. Do not pay the platform multiple for the Whale revenue. Structure the deal with a specific concentration earnout.

Split the EBITDA into two buckets:

As detailed in our guide to Structuring Earnouts That Pay Out, you can set terms where the seller receives the full value for the Whale only if that customer renews for 12-24 months post-close. If the customer churns, the buyer is protected.

Another lever is the "forgivable" seller note. Issue a seller note for 20% of the purchase price, with a specific covenant: if the Whale customer reduces spend by >15%, the note is forgiven dollar-for-dollar against the lost revenue. This aligns the founder's incentive to ensure a smooth handover.

Concentration doesn't have to be a deal-killer. But it requires an operator's eye to distinguish between a strategic partner and a single point of failure. Don't let the top-line ARR fool you—diligence the Whale until you know if it's an asset or an anchor.