You closed the deal 18 months ago. The 100-day plan was executed 'perfectly.' You consolidated the back office, aligned the sales compensation plans, and announced the synergy capture to the board. The EBITDA bridge looked solid.

So why are you missing the forecast for the third quarter in a row?

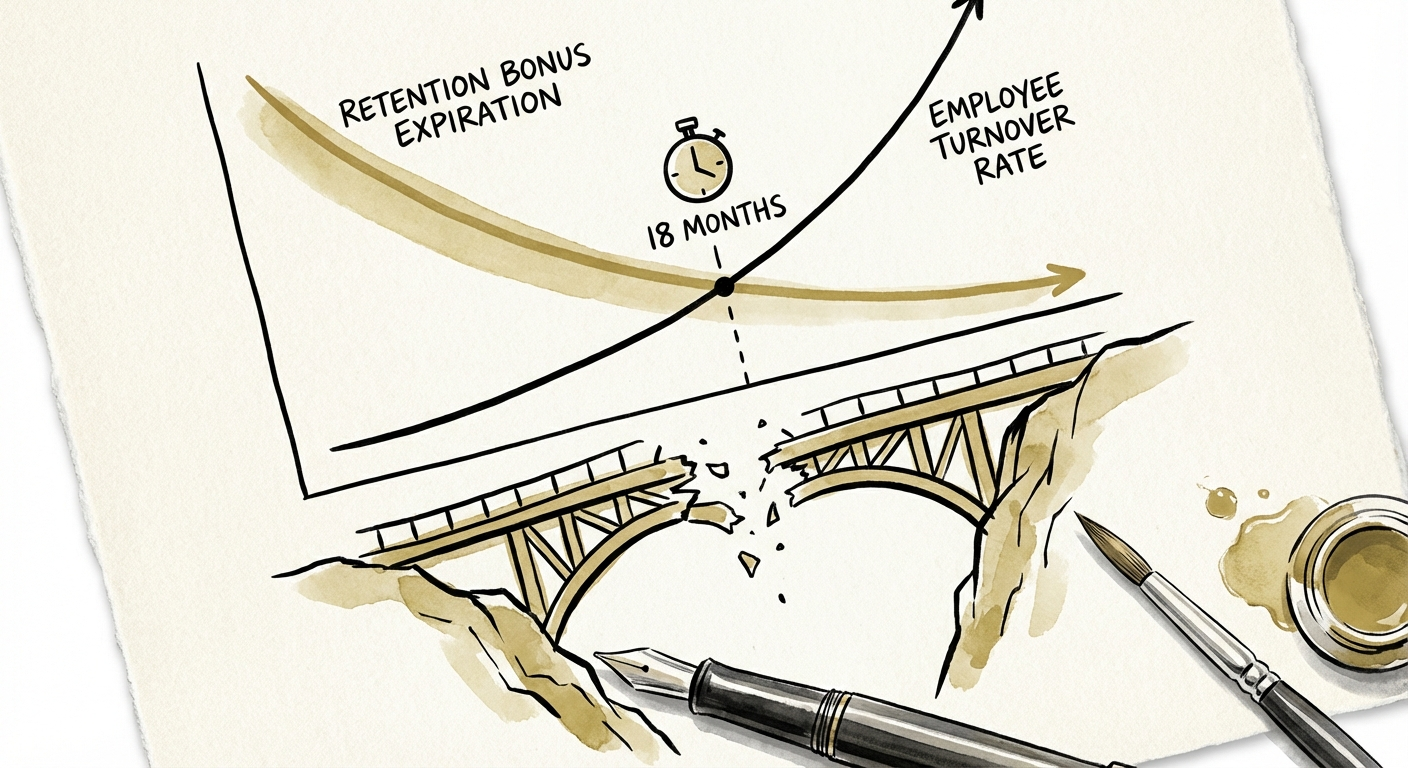

This is the 18-Month Integration Cliff. It is the specific moment when the 'tape and glue' used to hold the merged entity together begins to fail under the weight of daily operations. In the first year, adrenaline and financial engineering mask operational cracks. Retention bonuses keep key staff in their seats. Customers give you the benefit of the doubt.

But by month 18, the reality sets in. The 'integrated' platform is actually two legacy codebases talking via a fragile API. The 'unified' sales team is actually two warring tribes protecting their own territories. And the founders you paid to stay? Their earn-outs are vesting, and they are checking out.

You are not looking at a sales problem. You are looking at Integration Debt—the deferred operational maintenance you traded for speed at close. And unlike financial debt, this interest compounds daily in the form of customer churn and margin erosion.

When a portfolio company stalls at the 18-month mark, it is rarely bad luck. It is almost always one of three structural integration failures that were ignored during the first year.

Most PE sponsors model retention based on financial incentives. They assume that if the earn-out is 24 months, the talent is safe for 24 months. This is false.

Data from EY reveals that 47% of key employees leave within the first year of a merger, and 75% are gone by year three. The dangerous part is who leaves. It isn't the B-players; they cling to safety. It is the architects of the code, the relationship holders of the whale accounts, and the cultural carriers. By month 18, your 'retention' metrics might look stable on a spreadsheet, but the intellectual property has already walked out the door.

In the rush to show product synergies, technical teams often build 'facade integrations'—middleware layers that make two disparate systems look like one platform to the user. This works for the demo. It fails at scale.

By month 18, the technical debt accrued from maintaining two separate back-ends begins to strangle innovation. Instead of shipping new features, your engineering team is spending 60% of their cycles patching data synchronization errors between the legacy systems. This is why 30–50% of anticipated M&A value is lost due to slow or ineffective integration. You aren't getting the R&D leverage you paid for; you're paying double the maintenance cost for half the velocity.

You imposed your PE firm's reporting standards on Day 1. But did you standardize the delivery mechanics? Often, the acquired company continues to run on tribal knowledge while the parent company runs on SOPs. At month 18, as new hires replace the exited founders, that tribal knowledge evaporates. Suddenly, project margins collapse because the 'way we do things' wasn't documented—it was just in the head of a VP who left last month.

If you are seeing a performance dip at this specific interval, firing the VP of Sales will not fix it. You need to audit the integration you thought was finished.

The deal isn't done when the wire hits. The deal is done when the systems, culture, and processes are indistinguishable. Until then, you are just running two companies for the price of one—and that is a guaranteed way to kill EBITDA.